We have a group on campus called the “New Inklings Society.” It is based on an Oxford literary society from the 1940s with a similar name that was started by some of my favorite authors including J. R. R. Tolkien, and C. S. Lewis, and other professors of literature, philology, and philosophy. Like our namesake, we hold weekly discussions and talk about big ideas. We are a non-denominational, politically bipartisan society dedicated to civil conversation and human interaction. We have no criteria except a general belief in the existence of a single, immutable law of nature to which all things are bound. Our members major in any number of fields, from science and humanities, to visual arts and healthcare.

We have a group on campus called the “New Inklings Society.” It is based on an Oxford literary society from the 1940s with a similar name that was started by some of my favorite authors including J. R. R. Tolkien, and C. S. Lewis, and other professors of literature, philology, and philosophy. Like our namesake, we hold weekly discussions and talk about big ideas. We are a non-denominational, politically bipartisan society dedicated to civil conversation and human interaction. We have no criteria except a general belief in the existence of a single, immutable law of nature to which all things are bound. Our members major in any number of fields, from science and humanities, to visual arts and healthcare.

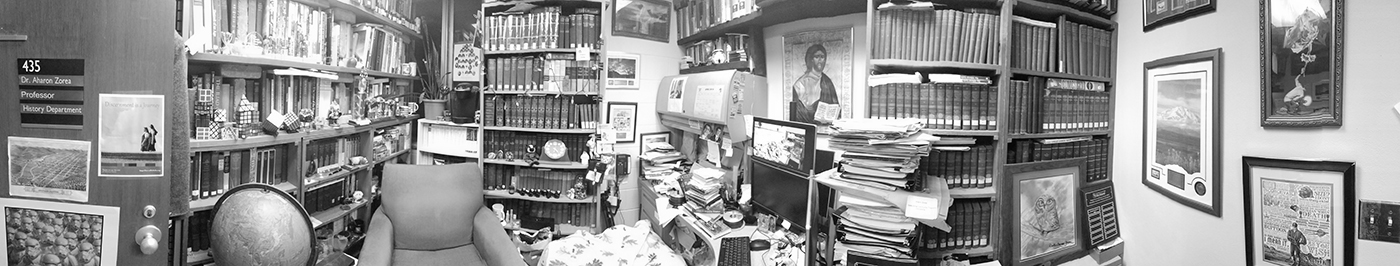

In practice, we gather together in a cozy room with cookies, treats, teas, coffees, and other light refreshments and just enjoy each other’s company. Students have an opportunity to relax, take their on-campus retreat for an hour, and share the warmth of communion with other students who share a similar philosophy on life. It is a joyful group.

We met last week, after a month off for our Christmas break and one of our members told the story of how her dog was recently hit by a car – it did not die, but was clearly hobbling. Despite his wounds, she remarked that he was “still a stinker” doing the same things he did before the accident, and acting in much the same way as if he had never been hit at all. She was surprised how the dog was not wallowing in the sorrows of his affliction. And clearly, she loved her dog. This story led to another anecdote from another member about how they had lost their pet when they were young, and how it was very hard for them – they really loved their pet. We are love our pets, and as a group we were certain that the pets truly loved them back.

But these stories inspired another question: Do they really love us? Do they have the capacity to truly love? Do animals have souls that can really love? Or… are we simply projecting our own love onto them, and reading their instinctual interactions as a sort of personal affection toward us?

I posed the question to the group, and almost all hands went up… yes, animals have souls, and yes, they truly love their humans. Then I asked, “But how do we know? What is the difference between a cat and a cow? Some animals we eat, and some we do not … do they all have souls? Are we be eating something that has a soul? How are our pets different than their agricultural cousins?”

The discussion that followed was relatively brief considering the subject matter. There were voices on all sides, but a few observations came out which I can summarize here:

- Not all animals share the same characteristics (pets are different than farm animals, and different from wild animals and from other living things, such as plants);

- Some animals do seem to genuinely love – and do so unconditionally, while others do not seem to love at all;

- The ability to love is not the only characteristic of a soul – just as there are different kinds of animals, so too it seems there are different kinds of souls.

Pets like dogs (and even cats) seem to love their owners, but they do not have reason or free will. They cannot choose between good or evil. Other animals, like goldfish or frogs, or even cows may be sweet and we may love them, but they do not seem to show genuine affection for their owners – it is hard to believe that our goldfish “loves” us. In some cases we may well be projecting our own emotions on our animals or pets, while in others we may be experiencing a genuine bond.

What is Love?

This lead to questions about the nature of love.

In an effort to describe love, I told the story of a time when I felt the distinct pain that comes only from love. One day while my wife Deb was in the hospital, just days before she passed away, I felt a genuine, physical tearing of some sort of invisible bond that was located in my heart. I had been sitting vigil with her for almost a month – I lived at the hospital with her, and spent every day by her side. My routine was to say a rosary around noon, and it had become almost a habitual action for me. During this time, I was not particularly emotional. I was in the “doing and helping” mode, and not in the “feeling” mode. Yet, on one particular day after I began my usual noon-time rosary, and just as I finished the first opening prayers, I felt myself start to cry uncontrollably – it was not intentional, I had not really cried hitherto, and it was certainly not what I wanted to do. To make matter more intense, almost at the same moment that I started crying in my prayers, one the women of our church came to visit Deb (who was sleeping, and had been sleeping for nearly three days). She saw that I was both praying the rosary and crying. She quietly sat down and joined me in my prayer. I was initially very self-conscious about it, but I seemed to have no choice – I was not going to stop the prayer, and I could not seem to stop crying.

I managed to make it through all five decades of the rosary, and as soon as I was finished I no longer felt a need to cry. It was over. Indeed, from that moment on I felt as if my heart had been released in some invisible and intangible way – it was like a physical tearing from my heart, but there was also carried a sense of “completion” about it. The whole experience was very real and very physical, and yet entirely intangible. I did not cry again until Deb’s funeral when I gave the eulogy, and I broke down at a particular line dealing with God’s purpose in Deb’s life — yet even that reaction was much more sedated. The breakdown that I experienced during my prayers at the hospital felt like a certain moment of transition, and once that transition had passed then I no longer felt compelled to pass through it again.

This was one of several experiences that convinced me that love was not just an emotion, nor even simple an act of will.

There is no question in my mind (and in my heart) that God grants and forges a physical bond between people who love each other. And that bond is not just limited to romantic love – parents share similar bonds with their children. Siblings share this with each other, as do good friends who love each other with a familial sort of intensity. It seems to me that it is a critical characteristic of the human heart. More precisely, I would say it is a reflection of the human soul. We can love, and we should love, and we suffer when we do not.

It was during the slow process of my wife’s death that I came to believe that life owes its ultimate meaning and purpose through love – that we are not only called to love as a duty of Christian charity, but that we are built to love as a function of our identity. A life without love is a life ill spent – and a life with love, no matter how humble or uneventful, is a life fulfilled.

To my Inklings, I explained that my prayerful tears at the deathbed of my wife was just one experience that proved to me that love involved emotional, intellectual, and physical bonds. I then shared another experience, which I feared might seem a bit trite in comparison. I shared it because it more directly related to the question of whether or not animals love and have souls. It involved the death of my cat, Frankie.

My first cat – at least the first cat that I personally took the initiative of searching for, purchasing, and taking of entirely on my own – my first cat lived to be nearly 17 years old. Her name was Frankie and she travelled with me from college to my first job, and joined our family after I married, and travelled with us from home to home as I was teaching and studying at graduate school. She was 16 years old during the year before I landed my first job as a college professor. We were living in Missouri and temporarily moved to Iowa before journeying further to Wisconsin. During our stay in Iowa, Frankie began showing signs of an advanced disease. I will not describe the symptoms, but it was clear that she was losing her ability to care for herself, and that she was dying.

My first cat – at least the first cat that I personally took the initiative of searching for, purchasing, and taking of entirely on my own – my first cat lived to be nearly 17 years old. Her name was Frankie and she travelled with me from college to my first job, and joined our family after I married, and travelled with us from home to home as I was teaching and studying at graduate school. She was 16 years old during the year before I landed my first job as a college professor. We were living in Missouri and temporarily moved to Iowa before journeying further to Wisconsin. During our stay in Iowa, Frankie began showing signs of an advanced disease. I will not describe the symptoms, but it was clear that she was losing her ability to care for herself, and that she was dying.

Deb and I talked about what to do, and decided that rather than let her suffer we would take her to the vet to have her put to sleep. I remember talking about it with Deb, and I remember being very rational about the whole situation. The boys were very young so they did not understand one way or the other, but I was quite stoic. I stood up to the task and promised to take the responsibility of driving Frankie to the vet myself, and then burying her in Grandma’s backyard after she was gone.

Deb was too sensitive to go with me, so I drove alone with Frankie to the vet. She sat next to me in the front seat – very still, and obviously struggling with something unseen. I drove with one hand on the wheel and the other stroking her fur during the 30 minutes it took to reach the vet’s office. I recall that throughout the entire drive, I was calm and quite logical and reasonable, and apparently unaffected by the event. I entered the vet’s office, explained why I was there, and I was very easy in my explanations. When they asked if I wanted to be present, I willingly agreed to accompany the vet into the back room where they were going to inject the drug that would put Frankie to sleep. I was handling the situation perfectly – both internally and externally.

Yet I remember vividly the moment after they injected Frankie and when I felt the life pass out of her. It was almost like an electric jolt. Immediately, I broke into an uncontrollable cry – it shocked me, and I think it shocked the vets. They quickly left the room and gave me time alone with Frankie. I did my best to stifle back the tears, but during the moment of her death I was unable to do so. It was only for a very brief moment – perhaps a minute – but it was physically jolting and I was genuinely taken aback by my own reactions. By the time the vets returned to the room, I was once again under control, and I never did experience the same wave of grief that I experienced during that brief moment. I felt as if a physical bond in my heart had been severed.

When I experienced the same reaction while my wife lay dying, I realized that the bond of love was more than just an intellectual or an emotional response. It is physical – invisible and intangible, yet absolutely physical. And clearly, it was not limited to human interactions.

I shared this story with the Inklings right after the story of praying with Deb. My point was that while we take for granted that a physical bond can exist between husband and wife, we are often skeptical about such bonds between humans and animals. It almost seems easier to describe our emotions as a simple projection of our own needs. That is how our discussion had begun.

Of Love and Souls

Do pets have souls? Can pets genuinely love? Can you forge a physical bond of love if the love is only one-sided? And…is this question even important?

Obviously, the bond with my wife was created from both ends – I loved her and she loved me in return. Is it unrealistic to assume the same was not true for the bond between myself and my pet Frankie? There are many different kinds of love, even between humans. Romantic love is only one type of bond, and it is only unique in that it is shared exclusively between two people (because it leads to the creation of new life, which requires a stable family). Other forms of love can also form from both ends. Familial love and the love of a strong friendship may be shared with multiple people, and (I believe) it is the highest form of love, precisely because it is not limited. As such, it best reflects the nature of God’s unconditional love, which is shared to all. Is it not unrealistic to believe that God might have created our pets as earthly vehicles for humans to experience a physical expression of unconditional love on earth? Is it possible that the bonds we share with our pets are also forge both from us and from them?

Obviously, the bond with my wife was created from both ends – I loved her and she loved me in return. Is it unrealistic to assume the same was not true for the bond between myself and my pet Frankie? There are many different kinds of love, even between humans. Romantic love is only one type of bond, and it is only unique in that it is shared exclusively between two people (because it leads to the creation of new life, which requires a stable family). Other forms of love can also form from both ends. Familial love and the love of a strong friendship may be shared with multiple people, and (I believe) it is the highest form of love, precisely because it is not limited. As such, it best reflects the nature of God’s unconditional love, which is shared to all. Is it not unrealistic to believe that God might have created our pets as earthly vehicles for humans to experience a physical expression of unconditional love on earth? Is it possible that the bonds we share with our pets are also forge both from us and from them?

It is not unreasonable… but I may also be crafting an argument from my own wish-fulfillment. So I looked up what the Church says on the subject.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church does not answer whether or not animals have souls, and I am not sure that we ever can answer such a question with absolute certitude. The Church does say unequivocally that all animals and all living things speak to the “integrity of Creation” (2415-2418, 2456-2457). In other words, God created animals, just as he created the plants and the rocks and everything in the material world with a specific purpose. They all fit together in a sort of unity, and together they all speak of God’s nature. Our Inkling’s Society is based on the conviction that there is a single order that transcends all Creation. In this case, animals share a bond with humans because they help humans better understand God – just as our understanding of chemistry, or biology, or mathematics may help us to better understand the intentional unity of the universe around us.

All creation has a purpose. We may not always recognize that purpose, and sometimes we may subvert that purpose for our own selfish ends. As Saint John Paul II wrote in his encyclical, Centesimus Annus, the goods of the Created world have their own purpose and man’s duty as steward of creation is to develop those goods to their natural end, and not for his own selfish desires. Animals are meant to be loved as well as to be eaten, and to be used for the benefit of mankind, which may include being used for testing when human testing might become dangerous. They should not be needlessly hurt, or dismissed. In his words, man should govern his use of all created resources with a “disinterested, unselfish and aesthetic attitude that is born of wonder in the presence of being and of the beauty which enables one to see in visible things the message of the invisible God who created them.” As the Catechism explains, “It is contrary to human dignity to cause animals to suffer or die needlessly. It is likewise unworthy to spend money on them that should as a priority go to the relief of human misery. One can love animals; one should not direct to them the affection due only to persons.” (2418)

So… do animals have souls? I believe yes… and no… and perhaps we will never know with quantifiable certainty while we still draw our breath.

Yes, they have souls in so far as they are alive and they have a capacity of love. They share a common characteristic of all living things in that they possess of spirit of life that in immaterial, cannot be created by human ingenuity, and which cannot be set back in place once it has left the physical body or form.

Do All Life Forms Have Souls?

How do plants differ from animals? They are both alive, but clearly there is a difference. Life is invisible and intangible, but it is very real and is essential for anything that moves, or grows, or takes in nutrition. At the same time, although plants and animals share the same sort of life force, they do not share consciousness. There is a difference between a “life force” and a “soul.” The life force (also only of God) is the basic necessity of anything that is not dead. The soul is that spirit that exists beyond simple living, which extends into the immaterial world, and contains some reflection of God’s love. These are not technical distinctions, but they seem to explain the difference between a tree and a bird, or a dog and an animal.

How do plants differ from animals? They are both alive, but clearly there is a difference. Life is invisible and intangible, but it is very real and is essential for anything that moves, or grows, or takes in nutrition. At the same time, although plants and animals share the same sort of life force, they do not share consciousness. There is a difference between a “life force” and a “soul.” The life force (also only of God) is the basic necessity of anything that is not dead. The soul is that spirit that exists beyond simple living, which extends into the immaterial world, and contains some reflection of God’s love. These are not technical distinctions, but they seem to explain the difference between a tree and a bird, or a dog and an animal.

We might say that a soul involves some sort of consciousness. Yet even in this aspect there are divisions. Not all animals share the same degrees of consciousness and that might distinguish between the types of animals. A tapeworm is utterly ignorant of its own existence, while a dog may be trained to react to any number of stimuli. A tapeworm does not love, but a dog does seem to (at least) imitate love. There is a perceptible difference in their characteristics of life, and so it makes sense to believe there is a difference in whether or not they have souls.

Dozens of real, albeit anecdotal, stories recount the love of a dog staying by its unconscious owner, or of sacrificing itself for the sake of its owner. We do not hear of such stories with tapeworms, or frogs, or even cows. The dogs do not necessarily act merely on a matter of instinctual alone, but when it sacrifices itself it seems to reflect something more than a genetic predisposition to protect itself and reproduce.

Yet again, not all of the “pet-like” animals love. A wild dog does not love humans. A feral cat, does not love humans. Yet, once the dog or the cat is domesticated, and shown constant and persistent attention (and love) from their humans, then they can show love. We might say that the animal’s capacity to love is nurtured and developed outside themselves – by their humans. Their humans, in turn, know how to love according to their divine nature bestowed by God. In this way, love always comes from outside oneself. An animal does not learn to love through evolution alone. Instead, it learns to love because humans show love to them first. This is the process of domestication. (There is a deeper allegory here about humans and God, which I will leave alone.) The point is that the expression of animal love seems to be triggered by the expression of human love. The house dog who loves you unconditionally has probably experienced a great deal of love from their owner since birth.

And again, not all animals seem to exhibit and equal capacity to love – even after domestication. As much as I love my goldfish, it will never be “domesticated” enough to love me back. Part of this is may be a reflection of their relative intelligence. Some sorts of animals exhibit a sense of “home.” Cows break from the pens all the time, and only return if they are driven back, or tempted back by food. They have no sense of “home,” they only know where their food is. But by contrast, dogs have been known to find their way back home even if they have been dropped off hundreds of miles away. Horses also seem to know their homes, and they also seem to love their owners. Goldfish, or frogs, or other kinds of animals that do not seem to love will enter the wild and be gone forever.

And again, not all animals seem to exhibit and equal capacity to love – even after domestication. As much as I love my goldfish, it will never be “domesticated” enough to love me back. Part of this is may be a reflection of their relative intelligence. Some sorts of animals exhibit a sense of “home.” Cows break from the pens all the time, and only return if they are driven back, or tempted back by food. They have no sense of “home,” they only know where their food is. But by contrast, dogs have been known to find their way back home even if they have been dropped off hundreds of miles away. Horses also seem to know their homes, and they also seem to love their owners. Goldfish, or frogs, or other kinds of animals that do not seem to love will enter the wild and be gone forever.

It seems that only certain animals have that capacity to love – we call them pets. If pet-like animals have a unique capacity for love, then that must reflect a different sort of life. Perhaps only the animals with certain kinds of souls have the capacity for love. Animals do not have free-will and they cannot choose between good decisions and evil ones – but they do seem to be able to love.

Skepticism of Love

Why does the question matter? It matters more than we might think. There is a popular sect within academic society of strict (meaning “atheistic”) evolutionists who believe that all life – whether human or tapeworm – is simply a sophisticated form of biological machinery. There is nothing immaterial or invisible about life. They do not believe in souls in any form of life. As such, they do not believe that anything exists outside the material realm. They are “skeptical” of anything that cannot be weighed, measured, or in some quantified by material means.

In plain English, these sorts of believers do not believe that there is any such thing as a divinely ordained love. They do not believe that there is anything immaterial about the bond of love between people, or animals. Love is simply a set of biological responses to certain types of stimuli. We call these emotional responses “love” but at heart, they can always be reduced to the collection of nervous, and hormonal interactions that are responsible for the creation of the emotional experience. From this perspective, love does not exist outside of that biological expression.

For Christians, as for any religiously minded person, such a mechanistic definition of love precludes any belief in self-sacrifice, or virtue, or honor, or duty, or anything that goes beyond purely self-interest (biological, or emotional, or otherwise). In my view, it is a rather cold view of the world. And if truth be known, I am seriously doubtful that anyone actually believes it – not even the strict evolutionists.

Anyone who has truly fallen in romantic love – or experienced familial love for children, or siblings, or parents – know deep down that their actions are not merely biological. We frequently do very irrational things while we are in love, and these things often do not serve our own interests, or in any way protect the propagation of our genetic material. We love because we choose to… even when it is hurts us to do so. That cannot be easily explained by biological impulses (though secular humanist scientists routinely attempt to do so).

Anyone who has truly fallen in romantic love – or experienced familial love for children, or siblings, or parents – know deep down that their actions are not merely biological. We frequently do very irrational things while we are in love, and these things often do not serve our own interests, or in any way protect the propagation of our genetic material. We love because we choose to… even when it is hurts us to do so. That cannot be easily explained by biological impulses (though secular humanist scientists routinely attempt to do so).

What does it mean? If we believe that animals have no souls… or for this discussion, if we believe that animals have no capacity to love anyone or anything, then are we setting ourselves up for material skepticism? If we believe that our interpretation of their love is merely a projection of our own hopes and desires – our own wish fulfillment – then do we run a dangerous risk of disbelieving in any kind of love?

If the love we feel for an animal, or from an animal, is merely a projection of our insecurities, then what does that say about the love we feel for, or from, another human? Is that also only a projection of our insecurities or emotional needs? Humans are entirely different from animals, and the love we feel for each other clearly seems to be of a different kind… but does that mean that our love for animals is less real?

Such skepticism is difficult to contain to just one sphere. If we only imagine our love for animals, then are we imagining our love for anything? Does anyone ever really love anyone else? Are our friends and spouses merely sophisticated versions of our pets, or are they just another insensitive object in our lives? Or… and this is perhaps most critical… what about our belief in other non-tangibles, such as divine revelation, sacramental grace, or even faith itself. It is an easy step to shift from questioning the realities of our feelings for small things and then transfer the same sort of questioning toward big things.

Again… for Christians and those of a religious mindset, love comes from God. I would argue that all love comes from God. It is not a biological property, or simply an emotion. Love is immaterial, which means it comes from outside this realm and outside ourselves. It is not physical only, nor is it emotional only, nor simply an act of will. Love transcends all three qualities of humanity.

Animal Love versus Human Love

Of course, we do not want to overstate the case. There are different kinds of love and humans do love differently than animals love. We have free will. We choose to love. It is not clear that animals – even our favorite pets – ever had the choice not to love us. They love us because God created them with that tendency, and we developed that love through domestication and training. It seems reasonable to suppose that the unconditional (yet developed) love of animals serves God’s will, and it helps humanity in some way. Unlike animals, we humans choose to love.

That means that there are times when we do not make that choice. There are times when we choose not to love.

We are, also, animals of a sort. We have physical animal bodies that are animated and brought to life with immaterial spiritual souls. It is foolish not to recognize both sides of our nature. As an animal body, we experience numerous biological tendencies that are completely unconscious to us – driven by hormones and other biological stimulus irrespective of human decision-making (our heart beats, our lungs breath, our stomach processes… all without being told to do so.) Many of our emotions are likewise animal based: we get moody when we are hungry, or tired; we get angry when we are hurt or surprised negatively. These are our animal reactions that we respond to without thinking.

We are, also, animals of a sort. We have physical animal bodies that are animated and brought to life with immaterial spiritual souls. It is foolish not to recognize both sides of our nature. As an animal body, we experience numerous biological tendencies that are completely unconscious to us – driven by hormones and other biological stimulus irrespective of human decision-making (our heart beats, our lungs breath, our stomach processes… all without being told to do so.) Many of our emotions are likewise animal based: we get moody when we are hungry, or tired; we get angry when we are hurt or surprised negatively. These are our animal reactions that we respond to without thinking.

Similarly, I think that we can sometimes love like animals love. There are certain times when we feel attachments to other people just because we are around them all the time. Like a dog who loves his owner, we form a shallow bond of friendship (or perhaps, “acquaintance-ship”) with someone that we work beside, live near, or generally share time with. At an animal level, the acquaintance relationship is unbidden, and often unacted upon. But we are human, and we can choose otherwise. It is within our power to leave the relationship as it is and to never go beyond that simple form of communion. Similarly, we may do the opposite. We can choose to develop bonds of friendship – perhaps even forge a bond of familial love with your friend. The free will gives us a greater capacity for love.

At the same time, the quality of free will in human love may also be destructive. We may choose to forge friendships, and can also choose to end those same relationships, or destroy the bond that tie them together. Dogs cannot do this, but humans can.

Dogs cannot sin, but humans can.

We are different from animals because our souls include free will and we must continually decide between following choices that lead to good or those that lead to evil. God calls us to “love our neighbor” – it is not just a mandate, but it is a central mission of our humanity. When asked about the greatest commandment of all, Jesus answers, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind. This is the great and first commandment. And a second is like it, you shall love your neighbor as yourself.” The first law is fulfilled in the second. As Jesus concludes, “On these two commandments depend all the law and the prophets.” We love God by loving our neighbor, because it is through the expression of material love that we see on earth that we can better understand our love for God, who is the source of all love.

We love God better when we love our friends, and our neighbors, and through a recognition of the integrity of Creation, we love God better when we love even our animals.

Our animal instincts may compel us to form attachments as a result of mere proximity and comfort, but we care called to transcend our animal instincts. As part of animal nature, we may react with anger when someone hits us, but we are called to forgive and respond with love. We have the gift of free will, and when we choose to not love, then we choose to break away from that medium of God’s presence, which He called us to embrace. Animals do not have these added responsibility, but we do.

Human souls are created with a level of moral accountability that animals do not share. That means that our love and our souls compel action. We are called to act, to love, and to transcend those base animal instincts that simple biology equips us with. We may develop a casual friendship with the person we spend time with, and we may choose to allow it to disappear as soon as our shared time is spent. But that is our choice as we are accountable for it. We may develop a true friendship and love with another, and yet still allow our own pride, or selfishness, or indifference to corrupt and destroy that friendship. We can choose to hide from the world, and shield ourselves from direct interaction (and love) from others. And when we do so, we open ourselves to a sort of judgement – whether divine or temporal is immaterial.

Conclusion

If we choose to love our pets, and yet do not exert at least the same level of effort to loving our neighbor, then we are accountable – not only to God, but to our own nature. We miss out on the gifts that such love produce. We live lives less full, when we choose not to develop our nature.

The animal side of us encourages us to love our friends, and to not love those who are unkind to us, or rude, or ugly (physically or otherwise). The animal side of our nature finds it easy to love if it satisfies our selfish desires – when it makes us feel good. It is an obedience to our divine nature (to our uniquely human soul) when we transcend those animal instincts and love someone who is not lovable, and not kind, and not beautiful. Obviously… we show our love in different ways (not all love is romantic – nor should even most of our love be romantic), but we should treat all people as our brothers and sisters. Even those who present a physical threat to us should be loved… if only through prayer. We are called to love even when it is difficult, and even when our animal natures do not want to.

Do animals have souls? Do my cats really love me? Yes, I believe they do, but there is no certainty.

At heart, like our faith itself, our conviction of love is a matter of personal assurance. I cannot prove that God loves me with quantifiable evidence, but I have so many personal experiences that have convinced me over and over again that He does. I believe that animals have and express love, and that we share in their love as one of the many wondrous reflections of God’s creation. Humans, though, as reflections of God’s image, enjoy a greater sort of love. And we should never miss the opportunities that such human exceptionalism provide.